|

Lenten Season & Easter

including Mardi Gras (Fat Tuesday),

Shrove Tuesday, Ash Wednesday, Palm Sunday, Maundy Thursday, Good Friday

and Easter

Lent, in Christian tradition, is the period of the liturgical year leading up to Easter.

The traditional purpose of Lent is the preparation of the believer  — through prayer, penitence, almsgiving and self-denial — for the annual commemoration during Holy Week of the Death and Resurrection of Jesus, which recalls the events linked to the Passion of Christ and culminates in Easter, the celebration of the Resurrection of Jesus Christ. — through prayer, penitence, almsgiving and self-denial — for the annual commemoration during Holy Week of the Death and Resurrection of Jesus, which recalls the events linked to the Passion of Christ and culminates in Easter, the celebration of the Resurrection of Jesus Christ.

Conventionally it is described as being forty days long, though different denominations calculate the forty days differently. The forty days represent the time that, according to the Bible, Jesus spent in the wilderness before the beginning of his public ministry, where he endured temptation by Satan.[1]

This practice was virtually universal in Christendom until the Protestant Reformation.[2] Some Protestant churches do not observe Lent, but many, such as Lutherans, Methodists, and Anglicans do.

In Western Christianity (with the exception of the Archdiocese of Milan which follows the Ambrosian Rite), Lent begins on Ash Wednesday and concludes on Holy Saturday [2] [3]. The six Sundays in Lent are not counted among the forty days because each Sunday represents a "mini-Easter", a celebration of Jesus' victory over sin and death.[1]

ORIGINS OF

LENT

The Lenten semi-fast may have originated for practical reasons: during the era of subsistence agriculture in the West as food stored away in the previous autumn was running out or had to be used before it went bad in store, and little or no new food-crop was expected soon (compare the period in Spring which British gardeners call the "hungry gap"). The Lenten semi-fast may have originated for practical reasons: during the era of subsistence agriculture in the West as food stored away in the previous autumn was running out or had to be used before it went bad in store, and little or no new food-crop was expected soon (compare the period in Spring which British gardeners call the "hungry gap").

The word "lent" came from the Anglo-Saxon lencten meaning "Spring (season)".[4] In Latin the term quadragesima (translation of the original Greek tessarakoste, the "fortieth day" before Easter) is used. This nomenclature is preserved in Romance, Slavic and Celtic languages (for example, Spanish cuaresma, Portuguese quaresma, French carême, Italian quaresima, Croatian korizma, Irish Carghas, and Welsh C(a)rawys). In the late Middle Ages, as sermons began to be given in the vernacular instead of Latin, the English word lent was adopted. This word initially simply meant spring (as in German language Lenz and Dutch lente) and derives from the Germanic root for long because in the spring the days visibly lengthen.[8]

STRUCTURE OF

LENT

There are traditionally forty days in Lent which are marked by fasting, both from foods and festivities, and by other acts of penance. The three traditional practices to be taken up with renewed vigour during Lent are prayer (justice towards God), fasting (justice towards self), and almsgiving (justice towards neighbour). Today, some people give up a vice of theirs, add something that will bring them closer to God, and often give the time or money spent doing that to charitable purposes or organizations.[9]

In many liturgical Christian denominations, Good Friday, Holy Saturday and Easter Sunday form the Easter Triduum.[10] Lent is a season of grief that necessarily ends with a great celebration of Easter. It is known in Eastern Orthodox circles as the season of "Bright Sadness." It is a season of sorrowful reflection which is punctuated by breaks in the fast on Sundays.

In the Roman Catholic Mass, Lutheran Divine Service, and Anglican Eucharist, the Gloria in Excelsis Deo is not sung during the Lenten season, disappearing on Ash Wednesday and not returning until the moment of the Resurrection during the Easter Vigil. On major feast days, the Gloria in Excelsis Deo is recited, but this in no way diminishes the penitential character of the season; it simply reflects the joyful character of the Mass of the day in question. It is also used in the Mass of the Lord's Supper. Likewise, the Alleluia is not sung during Lent; it is replaced before the Gospel reading by a seasonal acclamation. In the pre-1970 form of the Roman Rite omission of the Alleluia begins with Septuagesima.

Prior to 1970, the last two weeks of Lent were known as Passiontide, which began on what in the 1962 edition of the Roman Missal is called the First Sunday in Passiontide and in earlier editions Passion Sunday, but is now the Fifth Sunday in Lent. All statues (and in England paintings as well) in the church were veiled in violet. This was seen to be in accordance with the Gospel of that Sunday (John 8:46-59), in which Jesus “hid himself” from the people. The veils were removed at the singing of the Gloria during the Easter Vigil. Following Vatican II, and in the Reformed Kalendar of 1970, Passiontide was discontinued. Whether to maintain the tradition of veiling images is left to the decision of a country's conference of bishops.

In the Byzantine Rite, the Gloria (Great Doxology) continues to be used in its normal place in the Matins service, and the Alleluia appears all the more frequently, replacing "God is the Lord" at Matins.

FASTING & ABSTINENCE

Fasting during Lent was more severe in ancient times than today. Socrates Scholasticus reports that in some places, all animal products were strictly forbidden, while others will permit fish, others permit fish and fowl, others prohibit fruit and eggs, and still others eat only bread. In some places, believers abstained from food for an entire day; others took only one meal each day, while others abstained from all food until 3 o'clock. In most places, however, the practice was to abstain from eating until the evening, when a small meal without meat or alcohol was eaten. Even now, the Romanian, Coptic, Ethiopian and Eritrean Orthodox Churches continue the practice of avoiding all animal products including fish, eggs, fowl and milk sourced from animals (e.g. goats and cows as opposed to the milk of soy beans and coconuts) for the entire fifty-five days of their Lent.

During the early Middle Ages, meat, eggs and dairy products were generally forbidden. Thomas Aquinas argued that "they afford greater pleasure as food [than fish], and greater nourishment to the human body, so that from their consumption there results a greater surplus available for seminal matter, which when abundant becomes a great incentive to lust."[11]

However, dispensations for dairy products were given, frequently for a donation, from which several churches are popularly believed to have been built, including the "Butter Tower" of the Rouen Cathedral. In Spain, the bull of the Holy Crusade (renewed periodically after 1492) allowed the consumption of dairy products[12] and eggs during Lent in exchange for a contribution to the conflict.

Contemporary legislation is rooted in the 1966 Apostolic Constitution of Pope Paul VI, Paenitemini. He recommended that fasting be appropriate to the local economic situation, and that all Catholics voluntarily fast and abstain. He also allowed that fasting and abstinence might be substituted with prayer and works of charity.

Pursuant to Canon 1253, days of fasting and abstinence are set by the national Episcopal conference. On days of fasting, one eats only one full meal, but may eat two smaller meals as necessary to keep up one's strength. The two small meals together must sum to less than the one full meal. Parallel to the fasting laws are the laws of abstinence. These bind those over the age of fourteen. On days of abstinence, the person must not eat meat or poultry. According to canon law, all Fridays of the year, Ash Wednesday and several other days are days of abstinence, though in most countries, the strict requirements of abstinence have been limited by the bishops (in accordance with Canon 1253) to the Fridays of Lent and Ash Wednesday. On other abstinence days, the faithful are invited to perform some other act of penance.

Many modern Protestants consider the observation of Lent to be a choice, rather than an obligation. They may decide to give up a favorite food or drink (e.g. chocolate, alcohol) or activity (e.g., going to the movies, playing video games, etc.) for Lent, or they may instead take on a Lenten discipline such as devotions, volunteering for charity work, and so on. Roman Catholics may also observe Lent in this way in addition to the dietary restrictions outlined above, though observation is no longer mandatory under the threat of mortal sin. Many Christians who choose not to follow the dietary restrictions cite 1 Timothy 4:1-5 which warns of doctrines that "forbid people to marry and order them to abstain from certain foods, which God created to be received with thanksgiving by those who believe and who know the truth."

When observing fasting or abstinence during Lent, regard must be paid to the fact that Sundays are Feast Days, so there is no fast or abstinence. The days from Ash Wednesday to the day before Easter Sunday, excluding the Sundays, are forty, corresponding to the number of days Christ spent in the wilderness.

CARNIVAL /

FAT TUESDAY / SHROVE TUESDAY / MARDI GRAS

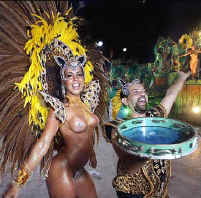

Carnival (Carnaval, Καρναβάλι (Carnavali), Carnevale, Carnestoltes, Carnaval, Karneval, Carnaval and Karnawał in Portuguese, Greek, Italian, Catalan, French, Dutch, German, Spanish and Polish languages) is a festive season which occurs immediately before Lent; the main events are usually during January and February. Carnival typically involves a public celebration or parade combining some elements of a circus, masque and public street party. People often dress up or masquerade during the celebrations, which mark an overturning of daily life. Carnival (Carnaval, Καρναβάλι (Carnavali), Carnevale, Carnestoltes, Carnaval, Karneval, Carnaval and Karnawał in Portuguese, Greek, Italian, Catalan, French, Dutch, German, Spanish and Polish languages) is a festive season which occurs immediately before Lent; the main events are usually during January and February. Carnival typically involves a public celebration or parade combining some elements of a circus, masque and public street party. People often dress up or masquerade during the celebrations, which mark an overturning of daily life.

Carnival is a festival traditionally held in Roman Catholic and, to a lesser extent, Eastern Orthodox societies. Protestant areas usually do not have carnival celebrations or have modified traditions, such as the Danish Carnival or other Shrove Tuesday events. The Brazilian Carnaval is one of the best-known celebrations today, but many cities and regions worldwide celebrate with large, popular, and days-long events. These include the Carnevale of Venice, Italy, the German Rhineland carnivals, centering on the Cologne carnival; the carnival of Santa Cruz de Tenerife, Canary Islands; the carnival of Cape Verde; of Torres Vedras, Portugal; Rio de Janeiro, Brazil; Rijeka, Croatia; Barranquilla, Colombia; Haiti; Jamaica; the Carnaval and the Llamadas in Montevideo, Uruguay and Trinidad and Tobago Carnival. In the United States, the famous Mardi Gras celebrations in New Orleans, Louisiana, and Mobile, Alabama, date back to French and Spanish colonial times. Carnival is a festival traditionally held in Roman Catholic and, to a lesser extent, Eastern Orthodox societies. Protestant areas usually do not have carnival celebrations or have modified traditions, such as the Danish Carnival or other Shrove Tuesday events. The Brazilian Carnaval is one of the best-known celebrations today, but many cities and regions worldwide celebrate with large, popular, and days-long events. These include the Carnevale of Venice, Italy, the German Rhineland carnivals, centering on the Cologne carnival; the carnival of Santa Cruz de Tenerife, Canary Islands; the carnival of Cape Verde; of Torres Vedras, Portugal; Rio de Janeiro, Brazil; Rijeka, Croatia; Barranquilla, Colombia; Haiti; Jamaica; the Carnaval and the Llamadas in Montevideo, Uruguay and Trinidad and Tobago Carnival. In the United States, the famous Mardi Gras celebrations in New Orleans, Louisiana, and Mobile, Alabama, date back to French and Spanish colonial times.

Shrove Tuesday is a term used in Ireland, the United Kingdom, Canada, New Zealand, and Australia for the day preceding Ash Wednesday, the first day of the Christian season of fasting and prayer called Lent. In England and many other countries, the festival was widely associated with the eating of rich foods made with eggs, sugar and butter, such as pancakes. It was often known simply as Pancake Day, originally because making such foods used up ingredients such as fat and eggs, whose consumption was traditionally restricted during fasting associated with Lent.

For German American populations, such as Pennsylvania Dutch Country, it is known as

Fastnacht Day (also spelled Fasnacht, Fausnacht, Fauschnaut, or Fosnacht). The Fastnacht is made from fried potato dough and served with dark corn syrup. In John Updike's novel Rabbit, Run, the main character remembers a Fosnacht Day tradition where the last person to rise would be teased by the other family members and called a "Fosnacht." For German American populations, such as Pennsylvania Dutch Country, it is known as

Fastnacht Day (also spelled Fasnacht, Fausnacht, Fauschnaut, or Fosnacht). The Fastnacht is made from fried potato dough and served with dark corn syrup. In John Updike's novel Rabbit, Run, the main character remembers a Fosnacht Day tradition where the last person to rise would be teased by the other family members and called a "Fosnacht."

In Hawaii, this day is also known as Malasada Day, which dates back to the days of the sugar plantations of the 1800s. The occupying Portuguese used up their butter and sugar prior to Lent by making large batches of malasada (doughnuts).

THE LENTEN SEASON HOLY DAYS

There are several holy days within the season of Lent.

Ash Wednesday is the first day of Lent in Western Christianity. In the Western Christian calendar, Ash Wednesday is the first day of Lent and occurs forty-six days (forty days not counting Sundays) before Easter. It is a moveable feast, falling on a different date each year because it is dependent on the date of Easter. It can occur as early as 4 February or as late as 10 March. Ash Wednesday gets its name from the practice of placing ashes on the foreheads of the faithful as a sign of repentance. The ashes used are gathered after the Palm Crosses from the previous year's Palm Sunday are burned. In the liturgical practice of some churches, the ashes are mixed with the Oil of the Catechumens[1] (one of the sacred oils used to anoint those about to be baptized), though some churches use ordinary oil. This paste is used by the minister who presides at the service to make the sign of the cross, first upon his or her own forehead and then on those of congregants. The minister recites the words: "Remember (O man) that you are dust, and to dust you shall return", or "Repent, and believe the Gospel."

Clean Monday (or "Ash Monday") is the first day in Eastern Orthodox Christianity. Clean Monday (Greek: Καθαρή Δευτέρα), also known as Pure Monday, Ash Monday, Monday of Lent or (in Cyprus only) Green Monday, is the first day of the Eastern Orthodox Christian and Eastern Catholic Great Lent. It is a movable feast that occurs at the beginning of the 7th week before Orthodox Easter Sunday. The common term for this day, "Clean Monday," refers to the leaving behind of sinful attitudes and non-fasting foods. It is sometimes called "Ash Monday," by analogy with Ash Wednesday (the day when the Western Churches begin Lent). The term is often a misnomer, as only a small subset of Eastern Churches practice the Imposition of Ashes. The Maronite Catholic Church is a notable Eastern rite that employs the use of Ashes on this day.

The fourth Lenten

Sunday, which marks the halfway point between Ash Wednesday and Easter, is sometimes referred to as

Laetare Sunday, particularly by Roman Catholics, and Mothering Sunday, which has become synonymous with Mother's Day in the United Kingdom. However, its origin is a sixteenth century celebration of the Mother Church. Laetare Sunday (pronounced /liːˈtɛəri/, or /leˈtɑre/ as in ecclesiastical Latin), so called from the incipit of the Introit at Mass, "Laetare Jerusalem" ("O be joyful, Jerusalem"), is a name often used to denote the fourth Sunday of the season of Lent in the Christian liturgical calendar. This Sunday is also known as Mothering Sunday, Refreshment Sunday, Mid-Lent Sunday (in French mi-carême), and Rose Sunday (because the golden rose sent by the popes to Catholic sovereigns used to be blessed at this time). The term "Laetare Sunday" is used predominantly, though not exclusively, by Roman Catholics and Anglicans. The word translates from the Latin laetare, singular imperative of laetari to rejoice.

The fifth Lenten

Sunday, also known as Passion Sunday (however, that term is also applied to Palm Sunday) marks the beginning of

Passiontide. Passion Sunday (Dominica de Passione) is the name that was given to the fifth Sunday of Lent in pre-1960 General Roman Calendar. In 1960 Pope John XXIII changed the official name to "First Sunday in Passiontide" (Dominica I in Passione) to fit with the name that his predecessor Pope Pius XII had given to Palm Sunday, calling it the "Second Sunday in Passiontide or Palm Sunday" (Dominica II in Passione seu in palmis). In 1969 Pope Paul VI removed the distinction between Passiontide and the general season of Lent, giving Palm Sunday the official full name of "Palm Sunday of the Passion of the Lord" (Dominica in Palmis de Passione Domini) and making what had been the First Sunday in Passiontide simply the Fifth Sunday in Lent. Some Anglicans and a minority of traditionalist Catholics continue to observe pre-1960 calendars, which use the older terminology, when the entire week beginning with the fifth Sunday of Lent was often called Passion Week prior to the calendar reform, which officially transferred that term to the following week; yet, as in the case of Palm Sunday, most Roman Catholic and Protestant laity alike continue to refer to the last week before Easter by its original name: Holy Week; indeed, this is the term employed in the Sacramentary and Lectionary of the Catholic Church.

When the term Passion Sunday is applied to the fifth Sunday of Lent, it marks the start of a two-week sub-season often referred to as Passiontide (and the formal name for it in the Roman Catholic calendar was actually the First Sunday of the Passion, in Latin Tempus Passionis).

Stations of the Cross (or Way of the Cross; in Latin, Via Crucis; also called the Via Dolorosa or Way of Sorrows, or simply, The Way (Latin for Way of Grief or Way of Suffering) ) refers to the depiction of the final hours (or Passion) of Jesus, and the devotion commemorating the Passion. It is currently marked by nine Stations of the Cross; there have been fourteen stations since the late 15th century, with the remaining five stations being inside the Church of the Holy Sepulchre.

The Stations themselves are usually a series of 14 pictures or sculptures depicting the following scenes:

-

Jesus is condemned to death

-

Jesus is given his cross

-

Jesus falls the first time

-

Jesus meets His Mother

-

Simon of Cyrene carries the cross

-

Veronica wipes the face of Jesus

-

Jesus falls the second time

-

Jesus meets the daughters of Jerusalem

-

Jesus falls the third time

-

Jesus is stripped of His garments

-

Crucifixion: Jesus is nailed to the cross

-

Jesus dies on the cross

-

Jesus' body is removed from the cross (Deposition or Lamentation)

-

Jesus is laid in the tomb and covered in incense.

The sixth Lenten

Sunday, commonly called Palm Sunday, marks the beginning of Holy Week, the final week of Lent immediately preceding Easter. Palm Sunday is a Christian moveable feast which always falls on the Sunday before Easter Sunday. The feast commemorates an event mentioned by all four Canonical Gospels Mark 11:1-11, Matthew 21:1-11, Luke 19:28-44, and John 12:12-19: the triumphant entry of Jesus into Jerusalem in the days before his Passion. It is also called Passion Sunday or Palm Sunday of the Lord's Passion. In many Christian churches, Palm Sunday is marked by the distribution of palm leaves (often tied into crosses) to the assembled worshipers. The difficulty of procuring palms for that day's ceremonies in unfavorable climates for palms led to the substitution of boughs of box, yew, willow or other native trees. The Sunday was often designated by the names of these trees, as Yew Sunday or by the general term Branch Sunday.

Wednesday of Holy Week is known as

Spy Wednesday to commemorate the days on which Judas spied on Jesus in the garden of Gethsemane before betraying him. In Christianity,

Holy Wednesday (also called Spy Wednesday, and in the Eastern and Oriental Orthodox Churches, Holy and Great Wednesday) is the Wednesday of the Holy Week, the week before Easter. It is followed by Maundy Thursday (Holy Thursday).

Thursday is known as

Maundy Thursday, or Holy Thursday, and is a day Christians commemorate the Last Supper shared by Christ with his disciples. Maundy Thursday, also known as Holy Thursday, Great and Holy Thursday, and Thursday of Mysteries, is the Christian feast or holy day falling on the Thursday before Easter that commemorates the Last Supper of Jesus Christ with the Apostles. It is the fifth day of Holy Week, and is preceded by Holy Wednesday and followed by Good Friday. The date is always between 19 March and 22 April inclusive. These dates in the Julian calendar, on which Eastern churches in general base their calculations of the date of Easter, correspond throughout the twenty-first century to 1 April and 5 May in the more commonly used Gregorian calendar. According to a common theory, the English word Maundy in that name for the day is derived through Middle English, and Old French mandé, from the Latin mandatum, the first word of the phrase "Mandatum novum do vobis ut diligatis invicem sicut dilexi vos" ("A new commandment I give unto you, That ye love one another; as I have loved you"), the statement by Jesus in the Gospel of John (13:34) by which Jesus explained to the Apostles the significance of his action of washing their feet. The phrase is used as the antiphon sung during the "Mandatum" ceremony of the washing of the feet, which may be held during Mass or at another time as a separate event, during which a priest or bishop (representing Christ) ceremonially washes the feet of others, typically 12 persons chosen as a cross-section of the community. According to other authorities, the English name "Maundy Thursday" arose from "maundsor" baskets, in which on that day the king of England distributed alms to certain poor at Whitehall: "maund" is connected with the Latin mendicare, and French mendier, to beg.[29][30] A source from the Missouri Synod of the Lutheran Church likewise states that, if the name were derived from the Latin mandatum, we would call the day Mandy Thursday, or Mandate Thursday, or even Mandatum Thursday; and that the term "Maundy" comes in fact from the Latin mendicare, Old French mendier, and English maund, which as a verb means to beg and as a noun refers to a small basket held out by maunders as they maunded. The name Maundy Thursday thus arose from a medieval custom whereby the English royalty handed out "maundy purses" of alms to the poor before attending Mass on this day.[31]

Good Friday follows the next day, on which Christians remember His crucifixion and burial. Good Friday, also called Holy Friday, Black Friday, or Great Friday, is a holiday observed primarily by adherents to Christianity commemorating the crucifixion of Jesus and his death at Calvary. The holiday is observed during Holy Week as part of the Paschal Triduum on the Friday preceding Easter Sunday, and often coincides with the Jewish observance of Passover.

Holy Week and the season of Lent, depending on denomination and local custom, end with Easter Vigil at sundown on Holy Saturday or on the morning of Easter Sunday. It is custom for some churches to hold sunrise services which include open air celebrations in some places. The Easter Vigil concludes with the celebration of the Eucharist (known in some traditions as Holy Communion). Certain variations in the Easter Vigil exist: Some churches read the Old Testament lessons before the procession of the Paschal candle, and then read the gospel immediately after the Exsultet. Some churches prefer to keep this vigil very early on the Sunday morning instead of the Saturday night, particularly Protestant churches, to reflect the gospel account of the women coming to the tomb at dawn on the first day of the week. These services are known as the Sunrise service and often occur in outdoor setting such as the church cemetery, yard, or a nearby park.

The first recorded "Sunrise Service" took place in 1732 among the Single Brethren in the Moravian Congregation at Herrnhut, Saxony, in what is now Germany. Following an all-night vigil they went before dawn to the town graveyard, God's Acre, on the hill above the town, to celebrate the Resurrection among the graves of the departed. This service was repeated the following year by the whole congregation and subsequently spread with the Moravian Missionaries around the world. The most famous "Moravian Sunrise Service" is in the Moravian Settlement Old Salem in Winston-Salem, North Carolina. The beautiful setting of the Graveyard, God's Acre, the music of the Brass Choir numbering 500 pieces, and the simplicity of the service attract thousands of visitors each year and has earned for Winston-Salem the soubriquet "the Easter City."

SOURCES:

Wikipedia and —

[1] ^ a b "What is Lent and why does it last forty days?". The United Methodist Church.

[2] ^ a b "The Liturgical Year". The Anglican Catholic

Church. Retrieved 2007-08-24.

[3] ^ Thurston, Herbert (1910), "Lent", The Catholic Encyclopedia,

IX, New York: Robert Appleton Company,

[4] ^ http://www.etymonline.com/index.php?search=Lent&searchmode=none

[8] ^ Online Etymology Dictionary, Lent. Retrieved 2009-03-08.

[9] ^ Spirit Home: Lent—disciplines and practices

[10] ^ General Norms for the Liturgical Year and the

Calendar, 19

[11] ^ Summa Theologica Q147a8.

[12] ^ Implicaciones económicas del miedo religioso en dos instituciones del Antiguo Régimen: la Inquisición y la Bula de Cruzada., Alejandro Torres Gutiérrez, Universidad Complutense de Madrid. Millennium:Fear and Religion.

[29] ^ Philip Schaff: History of the Christian Church, Volume III

[30] ^ Why is the Thursday preceding Easter known both as Holy Thursday and Maundy Thursday?

[31] ^ Shepherd of the Springs, Lutheran Church-Missouri Synod

Easter (Greek: Πάσχα) is the most important annual religious feast in the Christian liturgical year. According to Christian scripture, Jesus was resurrected from the dead on the third day of his crucifixion. Christians celebrate this resurrection on Easter Day or Easter Sunday (also Resurrection Day or Resurrection Sunday), two days after Good Friday and three days after Maundy Thursday. The chronology of his death and resurrection is variously interpreted to be between 26 and 36 AD. Easter also refers to the season of the church year called Eastertide or the Easter Season. Traditionally the Easter Season lasted for the forty days from Easter Day until Ascension Day but now officially lasts for the fifty days until Pentecost. The first week of the Easter Season is known as Easter Week or the Octave of Easter. Easter also marks the end of Lent, a season of fasting, prayer, and penance. Eastertide, or the Easter Season, or Paschal Time, is the period of fifty days from Easter Sunday to Pentecost Sunday.

Easter is a moveable feast, meaning it is not fixed in relation to the civil calendar. The First Council of Nicaea (325) established the date of Easter as the first Sunday after the full moon (the Paschal Full Moon) following the vernal equinox. Ecclesiastically, the equinox is reckoned to be on 21 March. The date of Easter therefore varies between 22 March and 25 April. Eastern Christianity bases its calculations on the Julian Calendar whose 21 March corresponds, during the twenty-first century, to 3 April in the Gregorian Calendar, in which calendar their celebration of Easter therefore varies between 4 April and 8 May.

ORIGINS/ETYMOLOGY

OF EASTER

Old English Ēostre (also Ēastre) and Old High German Ôstarâ are the names of a putative Germanic goddess whose Anglo-Saxon month, Ēostur-monath, has given its name to the Christian festival of Easter. Eostre is attested only by Bede, in his 8th century work De temporum ratione, where he states that Ēostur-monath was the equivalent to the month of April, and that feasts held in her honor during Ēostur-monath had died out by the time of his writing, replaced by the "Paschal month." The possibility of a Common Germanic goddess called *Austrōn-, reflecting the name of the Proto-Indo-European goddess of the dawn, was examined in detail in 19th century Germanic philology, by Jacob Grimm and others, without coming to a definite conclusion.

Subsequently scholars have discussed whether or not Eostra is an invention of Bede's, and produced theories connecting Eostra with records of Germanic Easter customs (including hares and eggs). Bede (pronounced /ˈbiːd/; Old English: Bēda), also Saint Bede, the Venerable Bede, or (from Latin) Beda (pronounced [beda]; 672/673–May 26, 735), was a monk at the Northumbrian monastery of Saint Peter at Monkwearmouth, today part of Sunderland, England, and of its companion monastery, Saint Paul's, in modern Jarrow (see Wearmouth-Jarrow), both in the Kingdom of Northumbria.

The English name for the festival of Easter derives from the Germanic word Eostre. It is only in Germanic languages that a derivation of Eostre marks the holiday. Most European languages use a term derived from the Hebrew pasch meaning Passover. In Spanish, for example, it is Pascua; in French, Pâques; in Dutch, Pasen; in Greek, Russian and the languages of most Eastern Orthodox countries: Pascha. In Middle English, the word was pasche, which is preserved in modern dialect words. Some languages use a term meaning Resurrection, such as Serbian Uskrs. Pope Gregory the Great ordered his missionaries to use old religious sites and festivals, and absorb them into Christian rituals where possible. The Christian celebration of the Resurrection of Christ was ideally suited to be merged with the Pagan feast of Eostre, and many of the traditions were adopted into the Christian festivities.[6]

Easter is linked to the Jewish Passover not only for much of its symbolism but also for its position in the calendar.

EASTER BUNNY

/ EASTER EGGS

Relatively newer elements such as the Easter Bunny and Easter egg hunts have become part of the holiday's modern celebrations, and those aspects are often celebrated by many Christians and non-Christians alike. There are also some Christian denominations who do not celebrate Easter.

The Easter Bunny (or Easter Hare) is a mythical character depicted as an anthropomorphic rabbit. In legend, the creature brings baskets filled with colored eggs, candy and toys to the homes of children on the night before Easter. The Easter Bunny will either put the baskets in a designated place or hide them somewhere in the house for the children to find when they wake up in the morning.

The Easter Bunny is very similar in trait to its Christmas holiday counterpart, Santa Claus, as they both bring gifts to good children on the night before their respective holiday. Its origin, mentioned in print as early as 1620,[1] can be traced to the German fertility goddess Ēostre. [2]

The Easter Bunny as an Easter symbol seems to have its origins in Alsace and southwestern Germany, where it was first mentioned in German writings in the 1600s. The first edible Easter Bunnies were made in Germany during the early 1800s and were made of pastry and sugar. The Easter Bunny was introduced to America by the German settlers who arrived in the Pennsylvania Dutch country during the 1700s.[3] The arrival of the "O_ster Haws_e" (a phonetic transcription of a dialectal pronunciation of the German Osterhase) was considered one of "childhood's greatest pleasures," similar to the arrival of Kriist Kindle (from the German Christkindl) on Christmas Eve. According to the tradition, children would build brightly colored nests,

often out of caps and bonnets, in secluded areas of their homes. The "O_ster Haws_e" would, if the children had been good, lay brightly colored eggs in the nest. As the tradition spread, the nest has become the manufactured, modern Easter basket, and the placing of the nest in a secluded area has become the tradition of hiding baskets.[4] often out of caps and bonnets, in secluded areas of their homes. The "O_ster Haws_e" would, if the children had been good, lay brightly colored eggs in the nest. As the tradition spread, the nest has become the manufactured, modern Easter basket, and the placing of the nest in a secluded area has become the tradition of hiding baskets.[4]

The egg was a symbol of the rebirth of the earth in Pagan celebrations of spring and was adopted by early Christians as a symbol of the rebirth. [5] The ancient Zoroastrians painted eggs for Nowrooz, their New Year celebration, which falls on the Spring equinox. The Nawrooz tradition has existed for at least 2,500 years. The decorated eggs are one of the core items to be placed on the Haft Seen, the Zoroastrian New Year display. The sculptures on the walls of Persepolis show people carrying eggs for Nowrooz to the king.

SOURCES: Wikipedia

and —

[1] ^ Billson, Charles J. (1892). Folklore. Harvard University: Folklore Society. p. 441.

[2] ^ MacMlchael, J Holden (1906). Notes and queries. Harvard University: Oxford University Press. p. 292.

[3] ^ Easter Symbols from Lutheran Hour Ministromy. Accessed 2/28/08]

[4] ^ http://www.lhmint.org/easter/symbols.htm

[5] Warwickshire County Council: The history of the Easter egg Retrieved on 2008-03-17

[6] england-in-particular: Easter Retrieved on 2008-03-14

Lent & Easter banner graphics

by Vanderbilt University

|

— through prayer, penitence, almsgiving and self-denial — for the annual commemoration during Holy Week of the Death and Resurrection of Jesus, which recalls the events linked to the Passion of Christ and culminates in Easter, the celebration of the Resurrection of Jesus Christ.

— through prayer, penitence, almsgiving and self-denial — for the annual commemoration during Holy Week of the Death and Resurrection of Jesus, which recalls the events linked to the Passion of Christ and culminates in Easter, the celebration of the Resurrection of Jesus Christ. The Lenten semi-fast may have originated for practical reasons: during the era of subsistence agriculture in the West as food stored away in the previous autumn was running out or had to be used before it went bad in store, and little or no new food-crop was expected soon (compare the period in Spring which British gardeners call the "hungry gap").

The Lenten semi-fast may have originated for practical reasons: during the era of subsistence agriculture in the West as food stored away in the previous autumn was running out or had to be used before it went bad in store, and little or no new food-crop was expected soon (compare the period in Spring which British gardeners call the "hungry gap").

Carnival (Carnaval, Καρναβάλι (Carnavali), Carnevale, Carnestoltes, Carnaval, Karneval, Carnaval and Karnawał in Portuguese, Greek, Italian, Catalan, French, Dutch, German, Spanish and Polish languages) is a festive season which occurs immediately before Lent; the main events are usually during January and February. Carnival typically involves a public celebration or parade combining some elements of a circus, masque and public street party. People often dress up or masquerade during the celebrations, which mark an overturning of daily life.

Carnival (Carnaval, Καρναβάλι (Carnavali), Carnevale, Carnestoltes, Carnaval, Karneval, Carnaval and Karnawał in Portuguese, Greek, Italian, Catalan, French, Dutch, German, Spanish and Polish languages) is a festive season which occurs immediately before Lent; the main events are usually during January and February. Carnival typically involves a public celebration or parade combining some elements of a circus, masque and public street party. People often dress up or masquerade during the celebrations, which mark an overturning of daily life.  Carnival is a festival traditionally held in Roman Catholic and, to a lesser extent, Eastern Orthodox societies. Protestant areas usually do not have carnival celebrations or have modified traditions, such as the Danish Carnival or other Shrove Tuesday events. The Brazilian Carnaval is one of the best-known celebrations today, but many cities and regions worldwide celebrate with large, popular, and days-long events. These include the Carnevale of Venice, Italy, the German Rhineland carnivals, centering on the Cologne carnival; the carnival of Santa Cruz de Tenerife, Canary Islands; the carnival of Cape Verde; of Torres Vedras, Portugal; Rio de Janeiro, Brazil; Rijeka, Croatia; Barranquilla, Colombia; Haiti; Jamaica; the Carnaval and the Llamadas in Montevideo, Uruguay and Trinidad and Tobago Carnival. In the United States, the famous Mardi Gras celebrations in New Orleans, Louisiana, and Mobile, Alabama, date back to French and Spanish colonial times.

Carnival is a festival traditionally held in Roman Catholic and, to a lesser extent, Eastern Orthodox societies. Protestant areas usually do not have carnival celebrations or have modified traditions, such as the Danish Carnival or other Shrove Tuesday events. The Brazilian Carnaval is one of the best-known celebrations today, but many cities and regions worldwide celebrate with large, popular, and days-long events. These include the Carnevale of Venice, Italy, the German Rhineland carnivals, centering on the Cologne carnival; the carnival of Santa Cruz de Tenerife, Canary Islands; the carnival of Cape Verde; of Torres Vedras, Portugal; Rio de Janeiro, Brazil; Rijeka, Croatia; Barranquilla, Colombia; Haiti; Jamaica; the Carnaval and the Llamadas in Montevideo, Uruguay and Trinidad and Tobago Carnival. In the United States, the famous Mardi Gras celebrations in New Orleans, Louisiana, and Mobile, Alabama, date back to French and Spanish colonial times. For German American populations, such as Pennsylvania Dutch Country, it is known as

Fastnacht Day (also spelled Fasnacht, Fausnacht, Fauschnaut, or Fosnacht). The Fastnacht is made from fried potato dough and served with dark corn syrup. In John Updike's novel Rabbit, Run, the main character remembers a Fosnacht Day tradition where the last person to rise would be teased by the other family members and called a "Fosnacht."

For German American populations, such as Pennsylvania Dutch Country, it is known as

Fastnacht Day (also spelled Fasnacht, Fausnacht, Fauschnaut, or Fosnacht). The Fastnacht is made from fried potato dough and served with dark corn syrup. In John Updike's novel Rabbit, Run, the main character remembers a Fosnacht Day tradition where the last person to rise would be teased by the other family members and called a "Fosnacht."

often out of caps and bonnets, in secluded areas of their homes. The "O_ster Haws_e" would, if the children had been good, lay brightly colored eggs in the nest. As the tradition spread, the nest has become the manufactured, modern Easter basket, and the placing of the nest in a secluded area has become the tradition of hiding baskets.[4]

often out of caps and bonnets, in secluded areas of their homes. The "O_ster Haws_e" would, if the children had been good, lay brightly colored eggs in the nest. As the tradition spread, the nest has become the manufactured, modern Easter basket, and the placing of the nest in a secluded area has become the tradition of hiding baskets.[4]